RFK: A Diamond In The Rough

[November 14th] -- Bud Selig wanted to make sure that there was no misunderstanding. A caller from Falls Church asked Selig, who was a guest on XM's MLB Homeplate program, "Commissioner, you could have moved the Expos to Norfolk, or Portland, or New Orleans, or any other city that doesn't have a baseball team. Why did you choose Washington? Did you feel guilty that we've lost two teams and you were trying to make things right?" There was a pause, then Selig replied, "We moved the Expos to Washington because D.C. had a stadium that was close to being major-league ready. None of the other cities had that."

[November 14th] -- Bud Selig wanted to make sure that there was no misunderstanding. A caller from Falls Church asked Selig, who was a guest on XM's MLB Homeplate program, "Commissioner, you could have moved the Expos to Norfolk, or Portland, or New Orleans, or any other city that doesn't have a baseball team. Why did you choose Washington? Did you feel guilty that we've lost two teams and you were trying to make things right?" There was a pause, then Selig replied, "We moved the Expos to Washington because D.C. had a stadium that was close to being major-league ready. None of the other cities had that."

Next question!

We owe a deep debt of thanks to RFK for bringing baseball back to town. Since opening day, however, it's been called "dilapidated," "decrepit" and "unworthy" to host major league baseball games.  True, it wasn't in the best of shape, but the $18 million dollar face lift it received made it "adequate" to its detractors, and a "great place to watch a game" for we baseball purists. Today, RFK Stadium is nothing more than a stop-gap, a place to play until the next greatest park is built, but when it first opened its doors, it was the most high-tech, state-of-the-art stadium in the United States.

True, it wasn't in the best of shape, but the $18 million dollar face lift it received made it "adequate" to its detractors, and a "great place to watch a game" for we baseball purists. Today, RFK Stadium is nothing more than a stop-gap, a place to play until the next greatest park is built, but when it first opened its doors, it was the most high-tech, state-of-the-art stadium in the United States.

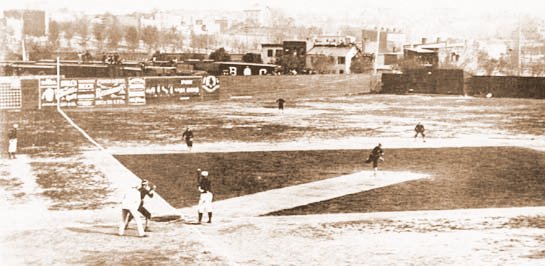

Griffith Stadium was one of the first steel and concrete baseball stadiums ever built. It replaced American League Park, a wooden structure that was at the time only three years old. By the 1950's, haphazard expansions and the Griffith family's tight-fisted nature made Griffith Stadium an eye-sore and a terrible place to watch a game. Congress began to consider the possibility of building a new, modern, dual purpose facility for the city, the first stadium specifically designed for two sports. Everyone loved the idea. Everyone except Calvin Griffith that is. The Griffiths owned both the Washington Senators and Griffith Stadium, and received a very nice income from the rent and concession and parking revenues generated from the Washington Redsk ins as well as other events. By playing in a new city owned stadium, Griffith would not only lose revenues but would also have to start paying rent, something the team had never had to do. Griffith asked for, and received permission to move the team just a few months after construction began on what would eventually become known as "D.C. Stadium." Upon hearing that news, Congress immediately threatened baseball with the removal of their anti-trust exemption and, almost immediately, the city of Washington was granted an expansion team to play in the new stadium.

ins as well as other events. By playing in a new city owned stadium, Griffith would not only lose revenues but would also have to start paying rent, something the team had never had to do. Griffith asked for, and received permission to move the team just a few months after construction began on what would eventually become known as "D.C. Stadium." Upon hearing that news, Congress immediately threatened baseball with the removal of their anti-trust exemption and, almost immediately, the city of Washington was granted an expansion team to play in the new stadium.

City officials wanted the new stadium to be "first class all the way," and engaged Osborn Engineering to build the structure. Osborn was the "HOK" of their day, having designed and built both Fenway Park and Yankee Stadium. City officials stressed that they didn't want an urban, quirky stadium with an unusual footprint.

Washington was a city of symmetry, and Osborn was given the task of coming up with something that mirrored Washington's uniqueness.

Washington was a city of symmetry, and Osborn was given the task of coming up with something that mirrored Washington's uniqueness.

Congress gave the Washington Fine Arts Commission final authority in all construction and design decisions. The commission was created in 1910, and charged with "meeting the growing need for a permanent body to advise the government on matters pertaining to the arts; and particularly, to guide the architectural development of Washington." Fountains, statues, monuments and memorials were all under the pervue of the commission. The height and size of buildings were strictly regulated. The commission looked at the new stadium as but another federal building in need of its guidance. It became a nightmare. Osborn would deliver designs to the commission who would then change much of what the architects had envisioned. The original light towers, for example, were "red lined" because they interfered with sightlines from the roof. By the time construction began, in July, 1960, the two sides were barely talking. Fifteen months later, the stadium was complete and ready for use.

D.C. Stadium was like no other facility when it opened. Unlike the other baseball parks, which were all built before there was a National Football League, D.C. Stadium was built with the Redskins in mind. The third base stands were built on a roller system which allowed the stands to be moved into centerfield for football games, lining both sides of the football field with high priced seats. There were broadcast booths for both sports, behind home plate for baseball and at the fifty yard line for football. The light banks were designed to illuminate both fields independently. In 1963, the $400,000 scoreboard was installed behind the right field fence.

D.C. Stadium remained unchanged throughout the 1960's.

The name was changed to R.F.K. Memorial Stadium after the Senator from New York was assassinated in 1968. In 1970, Vince Lombardi, new head coach of the Redskins, asked the D.C. Armory Board, managers of the stadium, to replace the grass field with astro-turf. They approved the request, but Senators' owner Bob Short refused, citing cost as the reason. The Senators left following the 1971 season, leaving the stadium to the Redskins. Over the next fifteen years, the stadium was kept clean, but little was done to keep the facility up to date. The "movable" stands rusted in place. A new scoreboard was installed in the right field upper deck, but was very plain when compared to the other NFL stadiums. When the Redskins left in 1997 for their new facility in suburban Maryland, D.C. United became the prime tenant. The city, and the soccer team, were unwilling, perhaps even unable, to invest any money into repairs and renovations for the now thirty-six year old stadium.

The name was changed to R.F.K. Memorial Stadium after the Senator from New York was assassinated in 1968. In 1970, Vince Lombardi, new head coach of the Redskins, asked the D.C. Armory Board, managers of the stadium, to replace the grass field with astro-turf. They approved the request, but Senators' owner Bob Short refused, citing cost as the reason. The Senators left following the 1971 season, leaving the stadium to the Redskins. Over the next fifteen years, the stadium was kept clean, but little was done to keep the facility up to date. The "movable" stands rusted in place. A new scoreboard was installed in the right field upper deck, but was very plain when compared to the other NFL stadiums. When the Redskins left in 1997 for their new facility in suburban Maryland, D.C. United became the prime tenant. The city, and the soccer team, were unwilling, perhaps even unable, to invest any money into repairs and renovations for the now thirty-six year old stadium.

R.F.K. Stadium cost $20 million dollars to build in 1961. The city of Washington sank $19 million into the facility earlier this year just to bring it up to code to placate the fire marshal as well as making it "good enough" for Bud Selig and major league baseball.

Just "good enough?" RFK was so good that cities all across the country copied the stadium's design. Atlanta, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, Cincinnati and Philadelphia built carbon copy facilities, and New York, San Diego and Houston created stadiums based on RFK's design.

So many cities copied RFK that the term "cookie cutter" became synonymous with RFK's circular symmetry and clean lines. Now, all those parks are either gone or are on their way out, and cookie cutter refers to all of the new, "old" look parks that have been built in the last decade.

So many cities copied RFK that the term "cookie cutter" became synonymous with RFK's circular symmetry and clean lines. Now, all those parks are either gone or are on their way out, and cookie cutter refers to all of the new, "old" look parks that have been built in the last decade.

RFK was the best of the circular stadiums. It wasn't patterned after anything else. It was unique. It was special. It was one of a kind. Just like the city it represents. I'll miss it when the Nationals move on.

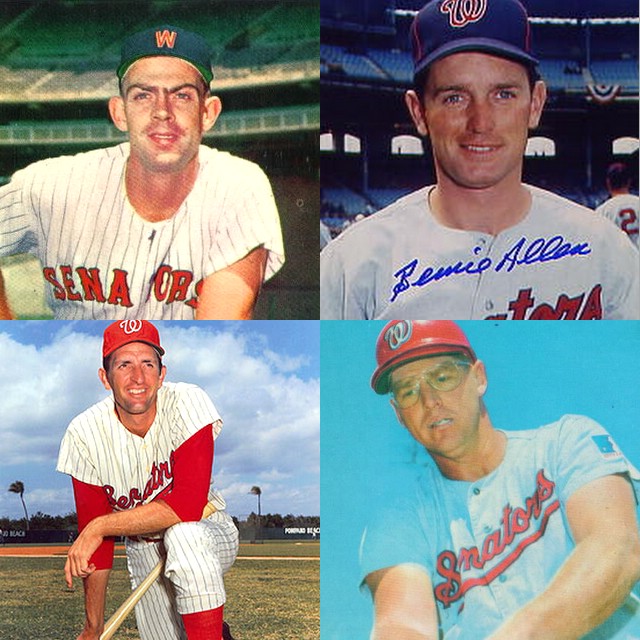

3) 1926 (road) --- 4) 1936-'37, 1948-'51

3) 1926 (road) --- 4) 1936-'37, 1948-'51 3) 1968 - '71, and 2005 (home) --- 4) 2005 (road)

3) 1968 - '71, and 2005 (home) --- 4) 2005 (road) Buddy Meyer --- Walter Johnson

Buddy Meyer --- Walter Johnson Ed Yost --- Muddy Ruel

Ed Yost --- Muddy Ruel Roger Peckinpaugh --- Joe Cronin

Roger Peckinpaugh --- Joe Cronin Del Unser --- Darold Knowles

Del Unser --- Darold Knowles Ed Stroud - Mike Epstein

Ed Stroud - Mike Epstein 3)1968 -- 4)1969 - 1971

3)1968 -- 4)1969 - 1971